Clinical Characteristics and Imaging Features of COVID-19 at Initial Diagnosis in Fever Clinic

-

摘要: 目的:探讨重型危重型新型冠状病毒感染者在门诊首诊时的临床特征和肺部CT表现。方法:回顾性分析发热门诊就诊的140例新型冠状病毒感染患者,其中中型组101例,重型危重型组39例。比较两组患者的一般人口学特征、临床表现、胸部薄层平扫CT(HRCT)检查及血常规+C反应蛋白(CRP)的差异性。结果:中型组和重型危重型组相比,①基线特征显示重型危重型组的年龄更高(66.05±14.38 vs. 77.90±13.12),首诊时病程更短(5.40±3.81 vs. 3.97±3.12),血氧饱和度(SPO2)更低(97.88±1.73 vs. 92.92±4.01),体温峰值(Tmax)更高(38.32±0.66 vs. 38.68±0.63);②肺部 CT显示重型危重型组的肺炎容积半定量更大(18.85±13.51 vs. 34.41±19.34);③血常规+CRP实验室检查显示重型危重型组的CRP更高(29.42±26.93 vs. 80.67±48.01),淋巴细胞计数(LYM)更低(1.64±0.68 vs. 0.95±0.64),粒细胞淋巴细胞比值更高(NLR)(3.48±2.46 vs. 9.36±10.42)。logistic回归分析显示年龄(OR=1.090,95%CI 1.006~1.181)、肺炎容积半定量(OR=1.086,95%CI 1.086~1.019)和SPO2(OR=0.261,95%CI 0.089~0.762)与新冠病毒感染重症危重症的发生相关,差异具有统计学意义;CRP(OR=1.054,95%CI 1.023~1.087)和LYM(OR=0.039,95%CI 0.04~0.391)与新冠病毒感染重症危重症的发生相关,差异具有显著统计学意义。结论:高龄、首诊时病程更短、SPO2更低、肺炎容积半定量更大、CRP升高、LYM下降与后期发展至新冠感染重型危重型相关,需要早期识别。Abstract: Objective: Objective: To explore and analyze the clinical features and chest thin-slice non-enhanced computed tomography (CT) imaging features of patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) at initial diagnosis in a fever clinic. Methods: A retrospective analysis was performed on 140 patients with COVID-19 at initial diagnosis in a fever clinic, including 101 and 39 cases in the moderate and severe and critical groups , respective-ly. Baseline, clinical characteristics, complete blood count + C-reactive protein (CBC+CRP), and chest thin-slice non-enhanced CT imaging characteristics of the patients were analyzed. Results: (1) The comparison between the moderate and severe and criti-cal groups showed that there were statistically significant differences in age (66.05±14.38 vs. 77.90±13.12,), course of initial diagnosis (5.40±3.81 vs. 3.97±3.12), SPO2 (97.88±1.73 vs. 92.92±4.01), and Tmax (38.32±0.66 vs. 38.68±0.63).(2) CT features between the two groups showed statistically significant differences in semi-quantitative volume (18.85±13.51 vs. 34.41±19.34). (3) The comparison between the moderate and severe and critical groups showed that there were statistically significant differ-ences in CRP (29.42±26.93 vs. 80.67±48.01), LYM (1.64±0.68 vs. 0.95±0.64), and NLR (3.48±2.46 vs. 9.36±10.42). (4) Six indicators, namely age, the course of initial diagnosis, SPO2, semi-quantitative volume, CRP, and LYM, were screened for multivariate logistic regression analysis. The result show that age (OR=1.090, 95%CI 1.006 ~ 1.181), semi-quantitative (OR=1.086, 95%CI 1.086 ~ 1.019), and SPO2 (OR=0.261, 95%CI 0.089 ~ 0.762), are related to the occurrence of severe and critical COVID-19 infection, and the difference is statistically significant; CRP (OR=1.054, 95%CI 1.023 ~ 1.087) and LYM (OR=0.039, 95%CI 0.04 ~ 0.391) are related to the occurrence of severe and critical COVID-19 infection, and the difference is significant statistically significant. Conclusion: Age, lower SPO2 and LYM, a shorter course; a higher Tmax, semi-quantitative volume, CRP, and NLR are associ-ated with severe and critical cases and required early identification.

-

Keywords:

- CT /

- COVID-19 /

- Omicron /

- clinical characteristics

-

SARS-CoV-2病毒引起的新型冠状病毒感染(COVID-19)3年来席卷全球。截至2023年5月5日,WHO宣布COVID-19不再构成国际关注的突发公共卫生事件[1]。

2022年12月以来的疫情主要为新型冠状病毒的变异株Omicron感染。Omicron变异株虽然致病毒力减弱,但免疫逃逸能力强,加上我国人口基数巨大,危重症感染患者的数值也不容小觑。本研究对我院发热门诊的首诊患者进行了回顾性分析,对其临床特点、肺部影像学特点和实验室检查等因素进行了深入研究,旨在提高首诊医师对新型冠状病毒感染的认识和危重症的早期识别,以利后期治疗,进一步降低死亡率。

1. 资料与方法

1.1 一般资料

本研究收集首都医科大学附属北京世纪坛医院2022年1月1日至2022年12月15日期间在发热门诊就诊的首诊患者中,确诊为新型冠状病毒感染且有肺部影像学表现的患者140例。所有患者均新冠核酸和/或新冠病毒抗原检测阳性,进行血常规+CRP检测及胸部薄层平扫CT检查。入组患者其中:男78例,女62例;年龄26~98岁,平均年龄(69.35±14.91)岁。所有患者于2023年3月通过医院HIS系统或电话完成随访工作,以确定最终的新冠病毒感染的病情分组。

本研究符合医学伦理学标准,并经作者医院研究伦理委员会审核。

1.2 诊断标准

COVID-19的诊断标准[2]:依据2023年1月5日《新型冠状病毒感染诊疗方案(试行第十版)》的诊断标准,有新冠病毒感染的相关临床表现;有新冠病毒核酸和/或抗原检测阳性。

纳入标准:所有患者符合《新型冠状病毒感染诊疗方案(试行第十版)》的诊断标准,新冠病毒核酸和/或抗原检测阳性。首诊时肺部CT提示肺炎表现。

排除标准:①首诊时没有完成血常规及肺部 CT检查者;②不能完成病情随访并进行新冠感染分型的患者;③胸部 CT模糊不清或显影有争议的患者;④存在急性血液系统疾病患者。

1.3 临床分型标准

轻型:以上呼吸道感染为主要表现,如咽干、咽痛、咳嗽、发热等。

中型:持续高热>3 d或(和)咳嗽、气促等,但呼吸频率(RR)<30次/min、静息状态下吸空气时指氧饱和度>93%。影像学可见特征性新冠病毒感染肺炎表现。

重型:成人符合下列任何一条且不能以新冠病毒感染以外其他原因解释:①出现气促,RR≥30次/分;②静息状态下,吸空气时指氧饱和度≤93%;③动脉血氧分压(PaO2)/吸氧浓度(FiO2)≤300 mmHg(1 mmHg=0.133 kPa);④临床症状进行性加重,肺部影像学显示24~48 h内病灶明显进展>50%。

危重型:符合以下情况之一:①出现呼吸衰竭,且需要机械通气;②出现休克;③合并其他器官功能衰竭需ICU监护治疗。

1.4 方法

1.4.1 标本采集及检测

血氧仪为鱼跃(YUWELL)血氧仪YX301指夹式脉氧饱和度仪。

1.4.2 血常规+CRP检测

血常规+CRP检测应用迈瑞5390-CRP血细胞分析仪。

1.4.3 CT扫描技术

CT扫描仪为32排的北京赛诺威盛Insitum-CT 338机型。

扫描参数:探测器宽度16 cm,螺距1.0,电压120 kV,电流150 mAs,重建层厚为肺窗1.5 mm和纵隔窗5 mm,矩阵是512×512,FOV 380~450。肺窗图像的窗宽和窗位为1600 HU和 -600 HU,纵隔窗的窗宽和窗位为400 HU和40 HU;并行冠状位和矢状位肺窗(1×5 mm)和纵隔窗(5×5 mm)重建;放射剂量DLP 500~600 mGy·cm。

1.4.4 影像分析

由两名中级医师独立完成,结果有分歧时由另一位高级医师协商。具体指标包括:累及部位、病变分布、病变密度和伴随病变。

1.5 统计学分析

根据第十版诊断标准,患者随访后,按病情转归分为两组:新冠中型组、重型和危重型组。比较两组患者的一般临床资料、影像学资料和血常规及CRP检查。数据采用SPSS 26.0软件进行统计分析。其中正态分布的计量资料采用均数±标准差(

$\bar x\pm s $ ),组间比较采用独立样本t检验;非正态分布的计量资料以中位数(四分位数)$(M(Q_L, Q_U)) $ 表示,采用秩和检验;计数资料采用频数和百分比n(%)表示,样本间采用卡方检验或Fisher精确检验。采用logistic回归模型分析影响新冠病毒感染重症危重症发生的危险因素。P<0.05表示差异有统计学意义,P<0.01表示差异有显著统计学意义。

2. 结果

140例COVID-19患者中,患者一般资料显示,中型组和重型危重型组比较,两者在年龄上有显著统计学差异(66.05±14.38 vs. 77.90±13.12),性别比例无差异。临床症状中,首诊时间2组有统计学差异(5.40±3.81 vs. 3.97±3.12),SPO2有统计学差异(97.88±1.73 vs. 92.92±4.01),体温峰值有统计学差异(38.32±0.66 vs. 38.68±0.63),发热、咳嗽、咽痛、胸闷、腹泻等症状均无统计学差异。中型组和重型危重型组比较,在感染高危因素中,显示高龄(≥65岁)(60.4% vs. 84.6%)和其他高危因素(2% vs. 12.8%)有统计学差异,肺部基础疾病、糖尿病、高血压、冠心病和肿瘤无统计学差异(表1)。

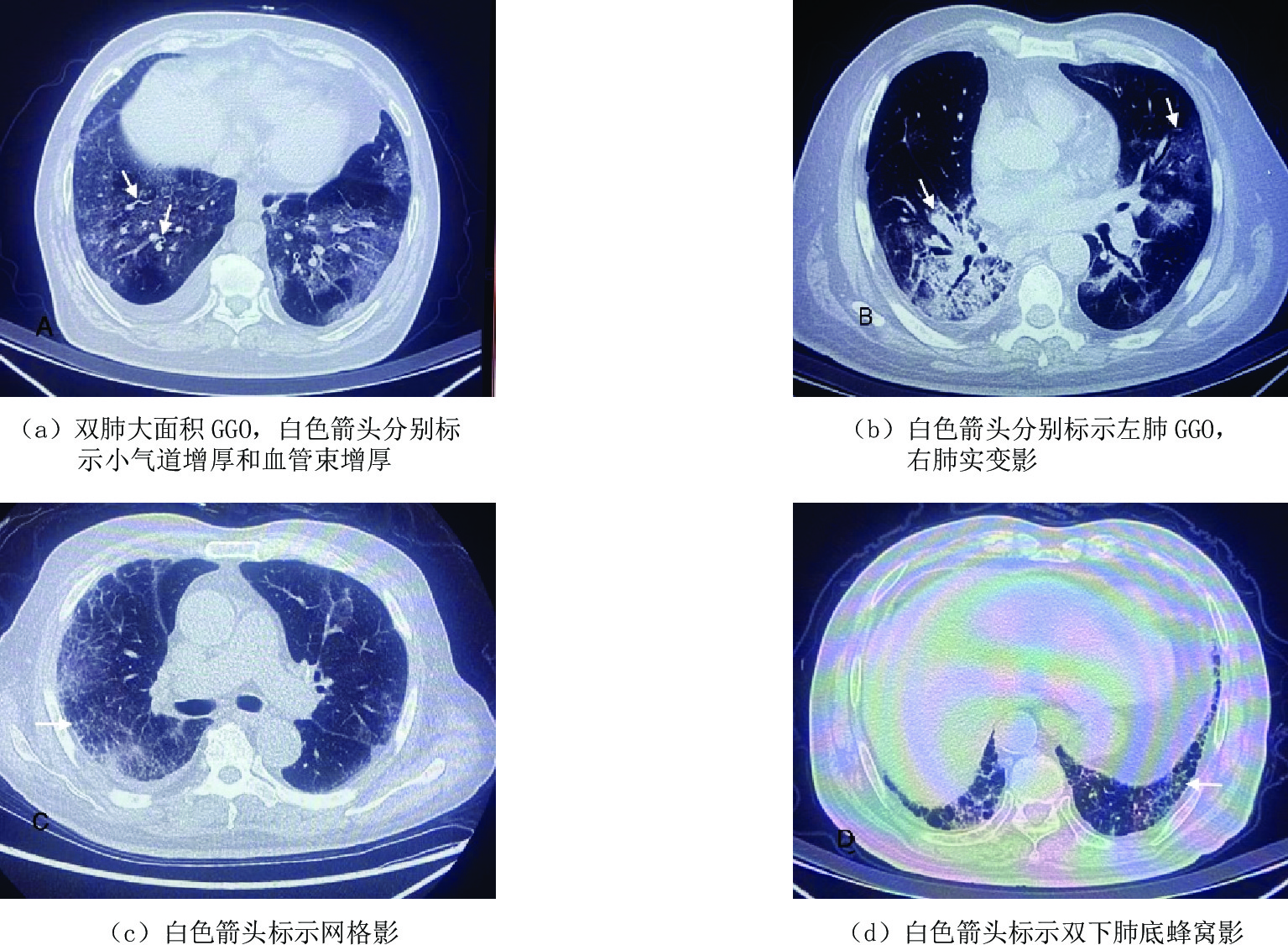

表 1 新型冠状病毒感染患者140例一般资料比较Table 1. Statistics of baseline and clinical characteristics of moderateand and severe and critical groups一般资料 中型组(n=101) 重型危重型组(n=39) 统计检验 $\chi^2/t $ P 性别(男)/例(%) 56(55.4) 22(56.4) 0.011 0.981 年龄/岁 66.05±14.38 77.90±13.12 -4.476 0.000** 临床症状 SPO2/% 97.88±1.73 92.92±4.01 3.285 0.004** 首诊时间/d 5.40±3.81 3.97±3.12 2.053 0.042* 发热/例(%) 99(99.0) 39(100.0) - 1.000 体温高峰/℃ 38.32±0.66 38.68±0.63 -2.575 0.012* 咳嗽/例(%) 87(86.1) 31(79.5) 0.940 0.332 咽痛/例(%) 33(32.7) 9(23.1) 1.234 0.267 胸闷/例(%) 8(7.9) 5(12.8) 0.326 0.568 腹泻/例(%) 8(7.9) 2(5.1) 0.044 0.834 高危因素 高龄(≥65岁)/(例%) 61(60.4) 33(84.6) 7.481 0.006** 肺部基础病/例(%) 9(8.9) 6(15.4) 0.649 0.421 糖尿病/例(%) 28(27.7) 15(35.8) 1.525 0.217 高血压/例(%) 31(30.7) 22(56.4) 7.910 0.050 冠心病/例(%) 18(17.8) 12(30.8) 2.810 0.094 肿瘤/例(%) 6(5.9) 3(7.7) 0.000 1.000 其高危因素(慢性肝病、肾病、维持性透析、晚期妊娠围产期、肥胖、重度吸烟)/例(%) 2(2.0) 5(12.8) 4.866 0.008** 注:*为P<0.05表示差异有统计学意义,**为P<0.01表示差异有显著统计学意义。 患者肺部CT特征显示,140例首诊的COVID-19患者,病变密度病变以磨玻璃影(ground-glass opacities,GGO)(131,93.5%)、实变影(62,44.3%)和网格影(113,80.7%)为主;病变分布多为双肺(121,86.4%)、下肺(62,44.3%)和周围为主(65,46.4%);伴随病变包括胸膜增厚(102,72.9%)、小气道壁增厚(103,73.6%)和血管束增厚(133,93.5%),胸腔积液(5,3.8%)少见。中型组和重型危重型组比较,两组在病变面积有显著统计学差异,容积半定量两组为(18.85±13.51 vs. 34.41±19.34)。具体影像学指标对照见表2,图1为病变密度、病变分布和伴随病变图片。

表 2 患者肺内病变HRCT征象比对Table 2. Comparison of abnormal pulmonary signs on CT in patients with COVID-19CT征象 总患者(n=140) 中型(n=101) 重型和危重型(n=39) 统计检验 $\chi^2/t $ P 病变密度/例(%) GGO为主 131(93.5) 93(92.1) 38(97.2) 1.930 0.165 实变影为主 62(44.3) 46(45.5) 16(41.0) 0.048 0.826 网格影为主 113(80.7) 79(78.2) 34(86.1) 1.473 0.225 蜂窝影为主 11(7.9) 10(9.9) 1(2.6) 5.632 0.018 病变分布/例(%) 0.619 0.431 双肺 121(86.4) 86(85.1) 35(89.7) 0.506 0.477 上肺为主 16(11.4) 12(11.9) 4(10.3) 0.000 1.000 下肺为主 62(44.3) 49(49.8) 13(33.3) 2.263 0.105 周围为主 65(46.4) 52(51.5) 13(33.3) 3.727 0.054 中央为主 25(17.9) 17(16.8) 8(20.5) 0.260 0.610 病变面积 9.201 0.002 容积半定量(%) - 18.85±13.51 34.41±19.34 -4.691 0.001** 面积>50%(例%) - 3(3.0) 14(35.9) 25.59 0.000** 伴随病变/例(%) 胸膜增厚 102(72.9) 72(71.7) 30(76.9) 0.452 0.501 小气道壁增厚 103(73.6) 75(74.3) 28(71.8) 0.767 血管束增厚 133(95.0) 94(93.1) 39(100) 0.210 胸腔积液 5(3.8) 4(4.0) 1(2.6) - 1.000 注:*为P<0.05表示差异有统计学意义,**为P<0.01表示差异有显著统计学意义。 患者血常规+CRP检查结果显示,中型组和重型危重型组比较,两组的CRP(29.42±26.93 vs. 80.67±48.01)、LYM(1.64±0.68 vs. 0.95±0.64)、NLR(3.48±2.46 vs. 9.36±10.42)、NLR>6.5(9.0% vs. 43.6%)均有显著统计学差异;NLR>3(44% vs. 92.3%)均有显著统计学差异;白细胞计数、NEU、PLT无统计学差异。实验室指标见表3。

表 3 中型组和重症危重症组实验室指标对比情况Table 3. Comparison of laboratory results in moderate and severe and critical groups检验项目 中型(n=101) 重型和危重型(n=39) 统计检验 $\chi^2/t $ P C反应蛋白/(mg/L) 29.42±26.93 80.67±48.01 -8.170 0.000** WBC/(×109/L) 6.85±2.25 7.29±3.60 -0.911 0.555 白细胞升高/例(%) 14(14) 7(17.9) 0.341 0.559 NEU/(×109/L) 4.96±3.71 5.77±2.96 -1.009 0.364 LYM/(×109/L) 1.64±0.68 0.95±0.64 5.412 0.000** NLR 3.48±2.46 9.36±10.42 -5.127 0.000** NLR>6.5/例(%) 9(9.0) 17(43.6) 22.080 0.000** NLR>3/例(%) 44(44) 36(92.3) 26.802 0.000** PLT/(×1012/L) 190.96±61.95 182.57±70.36 0.396 0.694 注:WBC为白细胞计数,NEU为中性粒细胞计数,LYM为淋巴细胞计数,PLT为血小板,NLR为中性粒细胞/淋巴细胞比值。*为P<0.05表示差异有统计学意义,**为P<0.01表示差异有显著统计学意义。 根据单变量分析结果及既往文献[3],我们筛选出年龄、首诊时间、SPO2、肺炎容积半定量、CRP、LYM等6项指标,进行多变量logistic回归分析。结果显示:年龄(OR=1.090,95%CI 1.006~1.181)、肺炎容积半定量(OR=1.086,95%CI 1.086~1.019)和SPO2(OR=0.261,95%CI 0.089~0.762)与新冠病毒感染重症危重症的发生相关,差异具有统计学意义;CRP(OR=1.054,95%CI 1.023~1.087)和LYM(OR=0.039,95%CI 0.04~0.391)与新冠病毒感染重症危重症的发生相关,差异具有显著统计学意义(表4)。

表 4 影响新型冠状病毒感染中型组及重型及危重型组的logistic回归分析结果Table 4. Logistic regression analysis in moderate and severe and critical groups变量 B值 SE值 Wald卡方值 OR值 95%CI P 年龄/岁 0.086 0.041 4.487 1.090 1.006~1.181 0.034* 首诊时间/d -0.203 0.144 1.967 0.817 0.615~1.084 0.161 SPO2 -1.345 0.547 6.039 0.664 0.664~0.350 0.014* 容积半定量 0.082 0.033 6.396 1.609 1.019~1.157 0.011* CRP 0.053 0.015 11.666 1.054 1.023~1.087 0.001** LYM -3.234 1.172 7.620 0.039 0.004~0.391 0.006** 注:*为P<0.05表示差异有统计学意义,**为P<0.01表示差异有显著统计学意义。 3. 讨论

新型冠状病毒感染(COVID-19)是一种新出现的严重的急性呼吸道传染病,自2019年末开始逐渐席卷全球。2020年1月30日,世界卫生组织(WHO)宣布将新冠疫情列为国际关注的突发公共卫生事件,同年3月11日,WHO宣布新冠疫情构成全球大流行(global pandemic)。虽然同为冠状病毒,COVID-19与严重急性呼吸综合征(SARS)和中东呼吸综合征(MERS)相比,重症和死亡率均明显降低。但截至目前,COVID-19的感染和死亡人数远远超过SARS和MERS[4]。

随着SARS-CoV-2在人群流行和传播,基因频繁发生突变。截止至2022年底,WHO提出的“关切的变异株(VOCs)”共有5个,依次以希腊字母表依序命名为Alpha、Beta、Gamma、Delta和Omicron。其中,Alpha变异毒株以高传播力为特征,Beta变异株有明显的人体免疫逃逸,而Gamma变异株以使既往感染者出现再次感染[5]。Delta变异株同时具备增加传染性和免疫逃逸两种特点的突变,传染性强,感染后感染者体内病毒载量高,清除速度慢。2021年11月首次在南非发现的Omicron(BA.1)变异株,在2022年为已经成为全球的主要流行株。

根据既往研究表明,相比新冠原始毒株,Omicron变异株表面的刺突蛋白(spike protein,S蛋白)有30个氨基酸被替换[6],包括R493、S496和R498在内的多个突变会在S蛋白和人类细胞受体ACE2之间产生新的盐桥和氢键,这些突变可能强化病毒与受体的结合能力或逃逸与中和抗体的结合能力。S蛋白的结构分析显示,突变所导致的与受体强结合能力的维持和与抗体逃逸能力增强,是Omicron迅速在全球传播的分子基础[7]。

Omicron变异株传播力和免疫逃逸能力增强,病毒致病力减弱,感染人体主要表现为咳嗽、发热、咽痛等,仅有少部分感染者会进展为肺炎。与Delta 变异株相比,Omicron的传染性增强,但住院率、危重症和死亡率均有降低。据中国疾病预防控制中心报告[8],新冠病毒感染本土病例病毒变异监测显示,全国均为Omicron变异株,共存在78个进化分支,北京以Omicron BF.7及其子分枝为优势株,而江苏BF.7及其子分支和BA.5.2及其子分支基本持平;其他省份均以BA.5.2及其子分支为优势株。

Omicron变异株,传播能力强、传播速度快、感染剂量低。虽然Omicron毒株所致的肺炎及重症率较低,但由于我国人口基数大,老龄化严重,存在感染高危因素人数巨大,另外,病毒在大基数人群中广泛传播,仍存在不断变异的可能,未来可能再次存在大量的新冠感染重症危重症的患者。

对于新型冠状病毒普通型患者,可以考虑根据有无高危因素,进行门诊口服药抗病毒治疗和居家观察。对于有可能发展至重症、危重症患者,则需尽早干预,尽快急诊留观或住院进一步治疗。在抗病毒治疗的基础上,必要时给予氧疗、激素、抗凝、呼吸机辅助支持等。如何在首诊时快速识别可能发展至危重症患者,对病情作出早期预判,既精准治疗患者,对重症危重症患者早期干预治疗,降低死亡率,又能对新型冠状病毒感染轻型中型患者合理治疗,节约医疗资源,使面对疫情患者激增时,有限的医疗资源得到高效利用,对发热门诊和急诊的首诊医师提出了要求。

本研究中,临床一般资料显示,新冠感染中型组和重型危重型组的年龄有显著统计学差异,增龄是独立的感染高危因素,这与既往研究一致[9-10]。两组的首诊时间有统计学差异(5.40±3.81 vs. 3.97±3.12),重症危重症组的患者从症状开始出现到首诊就医的平均时间更短,提示病情变化更迅速,这与疫情早期武汉观察到的数据结论一致[9]。两组的体温高峰有统计学差异(38.32±0.66 vs. 38.68±0.63),提示有危重症倾向的患者体内炎症反应更重。新冠感染除病毒本身对组织脏器的攻击破坏,感染引起的免疫风暴越来越多的引起人们的重视。而CRP、LY、体温高峰,甚至是病情进展的速度,均可以提示免疫风暴的风险性增加。重视CRP、LY、体温峰值,甚至是病情进展的速度,均有助于门诊医师迅速从大量患者中识别有可能进展为危重症的患者。

就诊时患者的SPO2和肺部CT显示的肺炎面积反映肺部病变的程度。正常SPO2为 95%~100%,当患者静息、未吸氧状态,SPO2为 90%~93%时,对应的PaO2在 60~70 mmHg[11],这时已经达到新冠感染重型的诊断标准,而患者未吸氧状态,SPO2<90%时,对应的PaO2在 60 mmHg以下[11-12],这就达到呼吸衰竭,新冠感染危重型的诊断标准[2]。SPO2通过小型便携式仪器方便易测、无创、重复性高。相比动脉血气分析检测,患者无痛苦依从性好,可持续检测,能及时准确的提供患者呼吸氧合参数[13],为门诊医生诊疗时提供可靠的判断依据。但检测时,需注意传感器的清洁度,避免选择测量血压时的肢体,指甲的长短和厚度,有无涂抹指甲油,局部组织的循环灌注、皮肤温度、手指颤动、贫血等情况都会影响的检测[13-14],从而干扰医生对病情的判断。

新型冠状病毒感染的肺部CT表现以疾病的病理改变为基础。SARS-CoV-2病毒引起的肺部损伤一种是病毒直接作用,另一重要原因是引起免疫风暴后,细胞因子对自身肺泡及肺间质的攻击。所以COVID肺部病变早期分布多以周围型、双肺、多发、延血管束分布为主,类似血管源性或继发性间质性病变。病变密度以边缘不清的均质或不均质的磨玻璃影为主,其内可见小气道壁增厚和血管束增厚。本研究入组患者均为我院发热门诊就诊的发病14 d内的首诊新冠病毒感染者,其肺部影像学变现与文献[15-16]及专家共识[2]相符。本研究中,中型和重型危重型组比较,肺炎容积半定量两组有明显统计学差异(18.85±13.51 vs. 34.41±19.34)。总体而言,病情的严重程度与肺炎的范围成正比,肺部炎症范围越大、病变组织占整体肺组织的体积比越大,则病情越严重。

据文献报道,CIOVID-19的生物学标志包括CRP、LYM、NLR等[17-18],这些指标能作为重症患者的预后危险因素预测指标[9]。本研究提示上述指标在新冠感染中型组和重症危重症组有显著统计学差异,说明早期简单的实验室检查即可提示。而在门诊首诊时,检查项目及检查时间都有限制,有些指标门诊难以实现,但血常规及分类+CRP是广泛应用,则更有现实的临床使用意义。本研究中,CRP在两组的标准差都比较大,提示CRP的离散程度较大。因为CRP本身为非特异性的炎症标志物,是在机体受到感染或组织损伤时血浆中一些急剧上升的蛋白质(急性蛋白),激活补体和加强吞噬细胞的吞噬而起调理作用,清除入侵机体的病原微生物和损伤、坏死、凋亡的组织细胞。在各种病原如病毒感染、细菌感染、不典型菌,手术后吸收热,及免疫病、肿瘤时均可升高。CRP在反映疾病严重程度和评价治疗反应方面具有很高的临床价值,指标的升高表明病毒感染后体内出现了过度炎症反应,往往预示着预后不良[10]。CRP在新冠肺炎疾病严重程度方面有很高的临床价值[19]但CRP并不是病毒感染引起的特异性指标。

本研究中,部分患者尤其是老年、有肺部基础病患者,同时存在白细胞升高,可能在SARS-CoV-2感染的同时合并存在着细菌感染,CRP升高有合并细菌感染的因素存在。由于门诊检查资料有限,我们并没有能完全除外合并的其他病毒、细菌的感染。同时,NEU、LYM和NLR的数据离散度也很大,我们考虑亦有此可能。

既往研究表明,新冠感染重症患者LYM减低,且淋巴细胞减少和死亡风险相关[3,10,20]。提示SARS-CoV-2病毒可作用于淋巴细胞,且作用机制与其他病毒感染后淋巴细胞增多不同。这与我们的结果一致。许多研究表明,NLR作为一个系统性炎症指标[18,21],和ICU的各种重症[22-23]、严重脓毒症死亡率[24-25]、ARDS预后明显相关[26],是一个良好的预测因素。Juan等的Meta分析显示,NLR与新冠感染重症及死亡率强相关[27-28]。同时,NLR>6.5可以作为一个切点,患者的死亡率更高[28]。Fei等[29]认为,NLR可作为新冠肺炎早期重症患者的一种独立预测生物学标志物,NLR的最佳截断值为3.00。这与我们的研究结果一致。NLR作为一炎症因子风暴的生物学标志物,可重复性高,费用低且患者接受程度高,是一个很好的预测性指标,能够帮助临床医生迅速鉴别潜在的危重症患者[30],及早干预,为下一步的治疗及分诊提供理论基础。这在发生医疗挤兑时尤为重要。

综上所述,SARS-CoV-2病毒Omicron变异株感染者,首诊时即存在肺部感染,则年龄、就诊时间、体温峰值、SPO2、CRP、LY、NLR和肺炎容积半定量等指标,均有助于医师迅速评价患者的病情走向,迅速从大量门诊就诊的患者中捡出重型/危重型患者,降低重症的发生率,降低疾病病死率。

本研究不足:作为回顾性单中心研究,统计时间较短,完整统计病例数目较少;没有统计新冠感染轻型患者,危重型新冠病毒感染危重型亦不能独立成组。这些有待于在今后扩大样本量、完善随访内容、延长随访时间、完善统计数据,以便今后进一步深入研究。

-

表 1 新型冠状病毒感染患者140例一般资料比较

Table 1 Statistics of baseline and clinical characteristics of moderateand and severe and critical groups

一般资料 中型组(n=101) 重型危重型组(n=39) 统计检验 $\chi^2/t $ P 性别(男)/例(%) 56(55.4) 22(56.4) 0.011 0.981 年龄/岁 66.05±14.38 77.90±13.12 -4.476 0.000** 临床症状 SPO2/% 97.88±1.73 92.92±4.01 3.285 0.004** 首诊时间/d 5.40±3.81 3.97±3.12 2.053 0.042* 发热/例(%) 99(99.0) 39(100.0) - 1.000 体温高峰/℃ 38.32±0.66 38.68±0.63 -2.575 0.012* 咳嗽/例(%) 87(86.1) 31(79.5) 0.940 0.332 咽痛/例(%) 33(32.7) 9(23.1) 1.234 0.267 胸闷/例(%) 8(7.9) 5(12.8) 0.326 0.568 腹泻/例(%) 8(7.9) 2(5.1) 0.044 0.834 高危因素 高龄(≥65岁)/(例%) 61(60.4) 33(84.6) 7.481 0.006** 肺部基础病/例(%) 9(8.9) 6(15.4) 0.649 0.421 糖尿病/例(%) 28(27.7) 15(35.8) 1.525 0.217 高血压/例(%) 31(30.7) 22(56.4) 7.910 0.050 冠心病/例(%) 18(17.8) 12(30.8) 2.810 0.094 肿瘤/例(%) 6(5.9) 3(7.7) 0.000 1.000 其高危因素(慢性肝病、肾病、维持性透析、晚期妊娠围产期、肥胖、重度吸烟)/例(%) 2(2.0) 5(12.8) 4.866 0.008** 注:*为P<0.05表示差异有统计学意义,**为P<0.01表示差异有显著统计学意义。 表 2 患者肺内病变HRCT征象比对

Table 2 Comparison of abnormal pulmonary signs on CT in patients with COVID-19

CT征象 总患者(n=140) 中型(n=101) 重型和危重型(n=39) 统计检验 $\chi^2/t $ P 病变密度/例(%) GGO为主 131(93.5) 93(92.1) 38(97.2) 1.930 0.165 实变影为主 62(44.3) 46(45.5) 16(41.0) 0.048 0.826 网格影为主 113(80.7) 79(78.2) 34(86.1) 1.473 0.225 蜂窝影为主 11(7.9) 10(9.9) 1(2.6) 5.632 0.018 病变分布/例(%) 0.619 0.431 双肺 121(86.4) 86(85.1) 35(89.7) 0.506 0.477 上肺为主 16(11.4) 12(11.9) 4(10.3) 0.000 1.000 下肺为主 62(44.3) 49(49.8) 13(33.3) 2.263 0.105 周围为主 65(46.4) 52(51.5) 13(33.3) 3.727 0.054 中央为主 25(17.9) 17(16.8) 8(20.5) 0.260 0.610 病变面积 9.201 0.002 容积半定量(%) - 18.85±13.51 34.41±19.34 -4.691 0.001** 面积>50%(例%) - 3(3.0) 14(35.9) 25.59 0.000** 伴随病变/例(%) 胸膜增厚 102(72.9) 72(71.7) 30(76.9) 0.452 0.501 小气道壁增厚 103(73.6) 75(74.3) 28(71.8) 0.767 血管束增厚 133(95.0) 94(93.1) 39(100) 0.210 胸腔积液 5(3.8) 4(4.0) 1(2.6) - 1.000 注:*为P<0.05表示差异有统计学意义,**为P<0.01表示差异有显著统计学意义。 表 3 中型组和重症危重症组实验室指标对比情况

Table 3 Comparison of laboratory results in moderate and severe and critical groups

检验项目 中型(n=101) 重型和危重型(n=39) 统计检验 $\chi^2/t $ P C反应蛋白/(mg/L) 29.42±26.93 80.67±48.01 -8.170 0.000** WBC/(×109/L) 6.85±2.25 7.29±3.60 -0.911 0.555 白细胞升高/例(%) 14(14) 7(17.9) 0.341 0.559 NEU/(×109/L) 4.96±3.71 5.77±2.96 -1.009 0.364 LYM/(×109/L) 1.64±0.68 0.95±0.64 5.412 0.000** NLR 3.48±2.46 9.36±10.42 -5.127 0.000** NLR>6.5/例(%) 9(9.0) 17(43.6) 22.080 0.000** NLR>3/例(%) 44(44) 36(92.3) 26.802 0.000** PLT/(×1012/L) 190.96±61.95 182.57±70.36 0.396 0.694 注:WBC为白细胞计数,NEU为中性粒细胞计数,LYM为淋巴细胞计数,PLT为血小板,NLR为中性粒细胞/淋巴细胞比值。*为P<0.05表示差异有统计学意义,**为P<0.01表示差异有显著统计学意义。 表 4 影响新型冠状病毒感染中型组及重型及危重型组的logistic回归分析结果

Table 4 Logistic regression analysis in moderate and severe and critical groups

变量 B值 SE值 Wald卡方值 OR值 95%CI P 年龄/岁 0.086 0.041 4.487 1.090 1.006~1.181 0.034* 首诊时间/d -0.203 0.144 1.967 0.817 0.615~1.084 0.161 SPO2 -1.345 0.547 6.039 0.664 0.664~0.350 0.014* 容积半定量 0.082 0.033 6.396 1.609 1.019~1.157 0.011* CRP 0.053 0.015 11.666 1.054 1.023~1.087 0.001** LYM -3.234 1.172 7.620 0.039 0.004~0.391 0.006** 注:*为P<0.05表示差异有统计学意义,**为P<0.01表示差异有显著统计学意义。 -

[1] WHO. Coronavirus (COVID-19) dashboard [EB/OL]. (2023-07-28) [2023-07-28]. https://covid19.who.int/.

[2] 中华人民共和国家卫生健康委会. 新型冠状病毒感染诊疗方案(试行第十版)[EB/OL]. (2023-01-05) [2023-01-05]. https://www.nhc.gov.cn. [3] HUANG C, WANG Y, LI X, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China[J]. Lancet, 2020, 395(10223): 497−506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5

[4] MAHASE E. Coronavirus: COVID-19 has killed more people than SARS and MERS combined, despite lower case fatality rate[J]. British Medical Journal, 2020, 18(368): m641.

[5] 张影, 李晓鹤, 陈凤, 等. 新型冠状病毒德尔塔和奥密克戎变异株感染患者的临床特征分析[J]. 新发传染病电子杂志, 2022, 7(3): 22-26. ZHANG Y, LI X H, CHEN F, et al. Clinical characteristics of patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 Delta and Omicron variants[J/CD]. Electronic Journal of Emerging Infectious Diseases, 2022, 7(3): 22-26. (in Chinese).

[6] BERKHOUT B, HERRERA-CARRILLO E. SARS-CoV-2 evolution: On the sudden appearance of the omicron variant[J]. Journal of Virology, 2022, 96(7):

[7] MANNAR D, SAVILLE J W, ZHU X, et al. SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant: Antibody evasion and cryo-EM structure of spike protein-ACE2 complex[J]. Science, 2022, 375(6582): 760−764. doi: 10.1126/science.abn7760

[8] 中国疾病预防控制中心. 全国新型冠状病毒感染疫情情况[EB/OL]. (2023-02-21) [2023-02-21]. https://www.chinacdc.cn/jkzt/crb/zl/szkb_11803/jszl_13141/202302/t20230218_263807.html. [9] 车霄, 王乐霄, 赵磊, 等. 重症新型冠状病毒肺炎患者的临床特征及预后风险因素分析[J]. 解放军医学院学报, 2023,44(2): 101−107. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.2095-5227.2023.02.001 CHE X, WANG L X, ZHAO L, et al. Clinical characteristics and prognostic factors of severe COVID-19[J]. Academic Journal of Chinese PLA Medical School, 2023, 44(2): 101−107. (in Chinese). doi: 10.3969/j.issn.2095-5227.2023.02.001

[10] GAO J, ZHANG S, ZHOU K, et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of patients with COVID-19 from a designated hospital in Hangzhou City: A retrospective observational study[J]. Hong Kong Medical Journal, 2022, 28(1): 54−63.

[11] 董宗祈, 朱达清, 黄开伟, 等. 无创氧饱和度换算动脉氧分压及其在儿科急救中的应用[J]. 实用儿科杂志, 1992,(1): 21−23. [12] 罗炎杰. 血气分析常用指标及其临床意义[J]. 中国临床医生, 2009,37(11): 30−33. [13] 韩文斌. 影响无创血氧饱和度监测值的相关因素[J]. 医疗卫生装备, 2011,32(7): 79−81. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1003-8868.2011.07.034 [14] 陆世琼, 王琼. 影响急诊患者无创脉搏血氧饱和度监测结果的非疾病因素的原因分析[J]. 中华高血压杂志, 2015,23: 91−92. [15] 孙莹, 李玲, 刘晓燕, 等. 早期新型冠状病毒肺炎的胸部薄层平扫CT表现特征[J]. CT理论与应用研究, 2023,32(1): 131−138. DOI: 10.15953/j.ctta.2023.006. SUN Y, LI L, LIU X Y, et al. Imaging features of early COVID-19 on chest thin-slice non-enhanced CT[J]. CT Theory and Applications, 2023, 32(1): 131−138. DOI: 10.15953/j.ctta.2023.006. (in Chinese).

[16] 李莉, 王珂, 任美吉, 等. 新型冠状病毒肺炎早期胸部CT表现[J]. 首都医科大学学报, 2020, 41(2): 174-177. LI L, WANG K, REN M J, et al. Early chest CT manifestations of COVID-19[J]. Journal of Capital medical University, 2020, 41(2): 174-177. (in Chinese).

[17] BATTAGLINI D, LOPES-PACHECO M, CASTRO-FARIA-NETO H C, et al. Laboratory biomarkers for diagnosis and prognosis in COVID-19[J]. Frontiers in Immunology, 2022.

[18] KARIMI A, SHOBEIRI P, KULASINGHE A, et al. Novel systemic inflammation markers to predict COVID-19 prognosis[J]. Front Immunol, 2021, 12: 741061. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.741061

[19] LUO X, ZHOU W, YAN X, et al. Prognostic value of C-reactive protein in patients with coronavirus 2019[J]. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 2020, 71(16): 2174−2179. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa641

[20] WANG D, HU B, HU C, et al. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China[J]. JAMA, 2020, 323(11): 1061−1069. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1585

[21] ZAHOREC R. Ratio of neutrophil to lymphocyte counts—rapid and simple parameter of systemic inflammation and stress in critically ill[J]. Bratisl Lek Listy, 2001, 102(1): 5−14.

[22] CANNON N A, MEYER J, IYENGAR P, et al. Neutrophil-lymphocyte and platelet-lymphocyte ratios as prognostic factors after stereotactic radiation therapy for early-stage non-small-cell lung cancer[J]. Journal of Thoracic Oncology, 2015, 10(2): 280−285. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0000000000000399

[23] BENITES-ZAPATA V A, HERNANDEZ A V, NAGARAJAN V, et al. Usefulness of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in risk stratification of patients with advanced heart failure[J]. The American Journal of Cardiology, 2015, 115(1): 57−61. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2014.10.008

[24] HWANG S Y, SHIN T G, JO I J, et a l. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio as a prognostic marker in critically-ill septic patients[J]. The American Journal of Emergency Medicine, 2017, 35: 234−239. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2016.10.055

[25] SARI R, KARAKURT Z, AY M, et al. Neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio as a predictor of treatment response and mortality in septic shock patients in the intensive care unit[J]. Turkish Journal of Medical Sciences, 2019, 49(5): 1336−1349. doi: 10.3906/sag-1901-105

[26] WANG Y, JU M, CHEN C, et al. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio as a prognostic marker in acute respiratory distress syndrome patients: A retrospective study[J]. Journal of Thoracic Disease, 2018, 10(1): 273−282. doi: 10.21037/jtd.2017.12.131

[27] ULLOQUE-BADARACCO J R, IVAN SALAS-TELLO W, AL-KASSAB-CORDOVA A, et al. Prognostic value of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in COVID-19 patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. International Journal of Clinical Practice, 2021, 75(11): e14596.

[28] PARTHASARATHI A, PADUKUDRU S, ARUNACHAL S, et al. The role of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in risk stratification and prognostication of COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Vaccines, 2022, 10(8): 1233. doi: 10.3390/vaccines10081233

[29] FEI M, TONG F, TAO X, et al. Value of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in the classification diagnosis of coronavirus disease 2019[J]. Zhonghua Wei Zhong Bing Ji Jiu Yi Xue, 2020, 32(5): 554−558.

[30] KUMAR A, SARKAR P G, PANT P, et al. Does neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio at admission predict severity and mortality in COVID-19 Patients? A systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Indian Journal of Critical Care Medicine, 2022, 26(3): 361−375. doi: 10.5005/jp-journals-10071-24135

-

期刊类型引用(0)

其他类型引用(1)

下载:

下载: